Ph.D. candidate encourages her class to judge a book by its cover

As a professional paper conservator and color science Ph.D. candidate, Leah Humenuck has studied books from every angle and wavelength. This semester, Humenuck is sharing her love for paper, ink, pigments, and all the material components of a book, in her course, The Secret Lives of Books, a special topics elective offered by the museum studies program in the College of Liberal Arts. She is gaining hands-on experience from the other side of the classroom, working with undergraduate students, sampling an academic career, and adding to her résumé. While the evolution of the book has been a global accomplishment, Humenuck focuses on book development in the Western world and the influence of parchment, which shaped the form, Gutenberg’s game-changing printing press, and the rise of paper. Her class teaches students how to assess a book through its materials and construction. Trends in book development point to available materials and choices often based in practicalities, she said. “There’s more than one way to read a book,” Humenuck said. She alternates her lectures with lab experiences that focus on handling rare books, mixing pigments, learning about book storage, and papermaking. “I think the best way to interact with history is to do the history,” Humenuck added. Christis Shepard, a fourth-year museum studies major from Bayonne, N.J., is enjoying the deep dive into the history of making books. “We’re currently learning about medieval books, the inks medieval scribes and artisans used, and the techniques used in creating parchment,” Shepard said. “It makes me appreciate the ease we have today in making books and that many of these old books managed to survive into the modern day.” Humenuck’s class meets in Wallace Library and frequently visits the Cary Graphic Arts Collection, RIT’s special collection of rare books, and graphic design and printing history. “I wanted to create a class that would intersect with the Cary Collection,” Humenuck said. “I tell my students, ‘While you’re here, use the Cary Collection because it’s phenomenal.’” Humenuck developed the special topics class at the suggestion of Juilee Decker, director of museum studies and co-director of the Cultural Heritage Imaging lab. Decker knew of Humenuck’s interest in an academic career.

Liam Myerow A student in the Secret Lives of Books course creates pigments in a medieval method by combining the powdered pigment with a binder in the glass jar.

“I enjoy tapping into what students are doing at the graduate level and seeing how they might inform what we’re doing in museum studies,” Decker said. “I thought that Leah’s expertise as a book and paper conservator would provide a materials perspective on a topic that is related to museum studies.” With a focus on libraries, archives, and museums, and a tech-infused approach to liberal arts and sciences, RIT’s museum studies program is one of the few undergraduate degree programs of its kind in the United States, Decker added. Interdisciplinary in nature, the program draws upon expertise from multiple colleges and divisions with a book niche. Steven Galbraith, curator of the Cary Graphic Arts Collection, teaches a course about the history of the book from a curatorial perspective, and faculty at the Image Permanence Institute offer a course about preservation and collections care. “Leah has served as a mentor and an internship supervisor for a number of my students,” Decker said. “I work with her in a research capacity, so I am aware of her excellent scholarship ethics and her keen eye toward mentoring and developing lifelong learning goals for people.” The path to becoming a college instructor is different for every Ph.D. student. The Secret Lives of Books is Humenuck’s first experience writing a syllabus and planning a curriculum for a semester-long class. Decker gave her guidance about classroom parameters and syllabi. She has also sat in on Humenuck’s classes. “It’s common that there’s not a precursor to teaching,” Decker said, reflecting on her doctoral degree at Case Western University. “There isn’t a formal class that says, ‘This is how you become an instructor now that you want to share your knowledge of this topic.’” The opportunity to teach builds upon Humenuck’s experience gained through her many guest lectures and talks, conference presentations, an internship program she created for museum studies, and her semester as a graduate teaching assistant for the Fundamentals of Color Science course. Christie Leone, assistant dean of the RIT Graduate School, said there are a lot of opportunities for graduate students to gain hands-on teaching experience by working as graduate teaching assistants under the supervision of a faculty mentor. Graduate teaching assistants are required to take a training course, GTA Foundations, offered by the Graduate School in collaboration with the Center for Teaching and Learning. The class provides basic background information and introduction to the responsibilities of a graduate teaching assistant at RIT. In addition, some colleges and departments offer their own training specific to their discipline. Humenuck’s class is giving her a multidisciplinary teaching experience. The elective has drawn 17 students from a variety of majors and with different opinions on materials for preserving information. “Being able to answer questions and pull a class together with students having different perspectives is something I really enjoy,” Humenuck said.

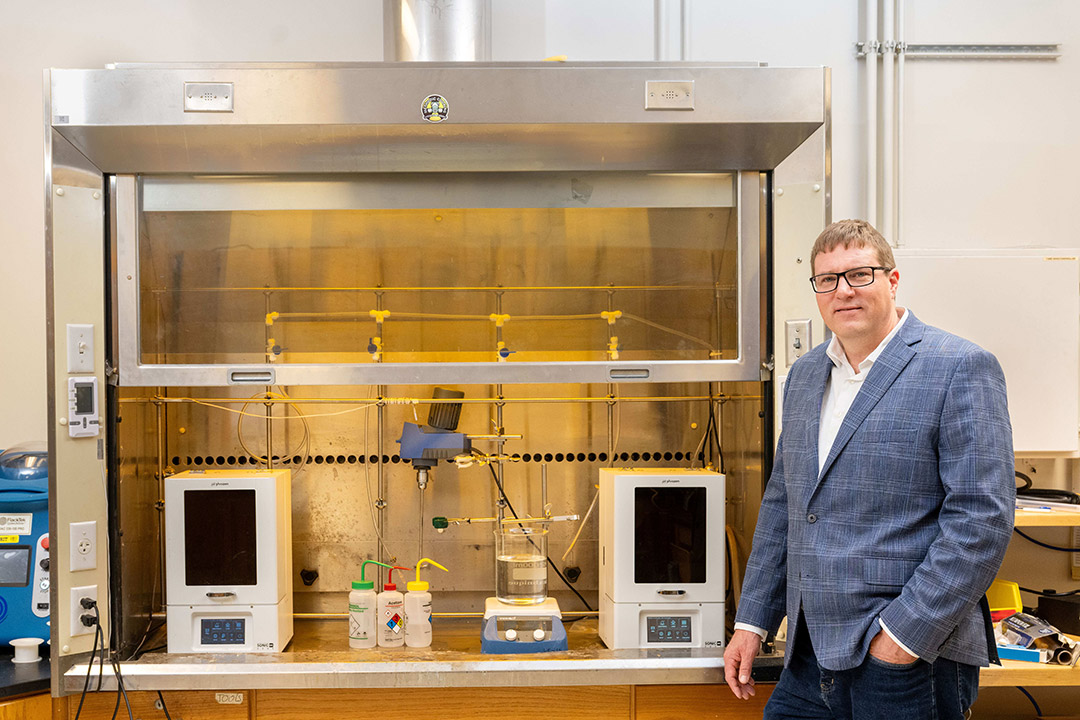

Researchers develop self-healing materials to improve 3D-printing processesSelf-healing materials are being developed by RIT researchers to further improve additive manufacturing, specifically 3D-printed products, to make them stronger and more resilient. Christopher Lewis and members of his research team developed a stimuli-responsive photopolymer solution—liquid resins similar in texture to superglue—that once printed exhibits the ability to self-heal when damaged, and through the lithography process, these liquid resins solidify selectively, layer-by-layer. There is a lot of interest today in materials that can heal, or self-repair, themselves. In 3D printing, the ability to build more reliable parts that have these healing actions can benefit multiple industries and provide cost savings. Companies can rely more confidently on the strength of materials being used for high-precision equipment such as printed electronics, soft robotics, or prosthetics for the aerospace, automotive, and biomedical fields, said Lewis, an associate professor and Russell C. McCarthy Endowed Professor in RIT’s College of Engineering Technology. “When you break a bone, or cut yourself, we take it for granted that there is a self-repairing mechanism that allows for bones or skin to rejuvenate themselves, at least to some extent,” said Lewis. “We also learn that it is not true for synthetic materials or man-made objects. And our work in self-healing materials is a futuristics look at how we can develop systems that mimic those natural material properties.” Peter Schuck/RIT Christopher Lewis, left, discussed the cellular nuances related to the self-healing resins with BS/MS student Kaia Ambrose. Ambrose is part of the team focused on shape memory behavior. Over time, 3D-printed objects can crack, particularly those used in load-bearing applications. This is worsened by the fact that many of the materials used in 3D printing are inherently brittle. Without intervention, the structures can fail. The team discovered that by combining a thermoplastic agent with an ultraviolet-curable resin enables a stronger 3D-printing process, while also creating a blend that reinforces cracked areas. “It makes the material much stronger than it used to be. One of the problems with these soft, elastomeric materials is that they are traditionally weak. And it also engenders another type of property—shape memory behavior, and we are just starting to focus our efforts on better understanding this behavior,” said Lewis. At the forefront of this work for several years, Lewis received funding from the U.S. Department of Defense and partnered with scientists in RIT’s AMPrint Center to test how self-healing materials supplement 3D-print processes. He and co-authors Vincent Mei and Kory Schimmelpfennig, RIT doctoral students, detailed the work in several journals including ACS Applied Polymer Materials, Polymer, and a recent issue of 3D Print Industry. Each highlights the team’s focus on the UV-vat polymerization of this liquid resin system. The challenges, he said, are in regulating the viscosity of the reactive resin, and ensuring all materials are soluble and light sensitive. “The approach we have taken is one where we have a mixture of two different things. We have our photoreactive, thermosetting polymer that once cured becomes a soft rubber. To this, we also add a thermoplastic healing agent. We were able to get light to pass through the system, and we achieved that by utilizing polymerization induced phase separation (PIPS). It is a process where the thermoset and thermoplastic materials separate during curing,” he said. “That is key to this whole thing.” PIPS is a single, segmented function where an optically transparent liquid allows light to pass through. By curing the UV resin, the thermoplastic phase separates. Lewis compared that final phase-separated structure to a lava lamp that changes as it is lit or heated. It is similar with the polymers that transform as they are integrated with the 3D-print as each layer is cured. “Earlier work on thermoplastic polymer blends that are able to be processed using conventional techniques like injection molding or extrusion suggested that it was that phase separation that seemed to be driving the self-healing behavior of those systems. That understanding led us down this path of experimentation with this same healing agent and photo reactive polymer system, and then, a little bit of luck,” said Lewis.

Researchers develop self-healing materials to improve 3D-printing processesSelf-healing materials are being developed by RIT researchers to further improve additive manufacturing, specifically 3D-printed products, to make them stronger and more resilient. Christopher Lewis and members of his research team developed a stimuli-responsive photopolymer solution—liquid resins similar in texture to superglue—that once printed exhibits the ability to self-heal when damaged, and through the lithography process, these liquid resins solidify selectively, layer-by-layer. There is a lot of interest today in materials that can heal, or self-repair, themselves. In 3D printing, the ability to build more reliable parts that have these healing actions can benefit multiple industries and provide cost savings. Companies can rely more confidently on the strength of materials being used for high-precision equipment such as printed electronics, soft robotics, or prosthetics for the aerospace, automotive, and biomedical fields, said Lewis, an associate professor and Russell C. McCarthy Endowed Professor in RIT’s College of Engineering Technology. “When you break a bone, or cut yourself, we take it for granted that there is a self-repairing mechanism that allows for bones or skin to rejuvenate themselves, at least to some extent,” said Lewis. “We also learn that it is not true for synthetic materials or man-made objects. And our work in self-healing materials is a futuristics look at how we can develop systems that mimic those natural material properties.” Peter Schuck/RIT Christopher Lewis, left, discussed the cellular nuances related to the self-healing resins with BS/MS student Kaia Ambrose. Ambrose is part of the team focused on shape memory behavior. Over time, 3D-printed objects can crack, particularly those used in load-bearing applications. This is worsened by the fact that many of the materials used in 3D printing are inherently brittle. Without intervention, the structures can fail. The team discovered that by combining a thermoplastic agent with an ultraviolet-curable resin enables a stronger 3D-printing process, while also creating a blend that reinforces cracked areas. “It makes the material much stronger than it used to be. One of the problems with these soft, elastomeric materials is that they are traditionally weak. And it also engenders another type of property—shape memory behavior, and we are just starting to focus our efforts on better understanding this behavior,” said Lewis. At the forefront of this work for several years, Lewis received funding from the U.S. Department of Defense and partnered with scientists in RIT’s AMPrint Center to test how self-healing materials supplement 3D-print processes. He and co-authors Vincent Mei and Kory Schimmelpfennig, RIT doctoral students, detailed the work in several journals including ACS Applied Polymer Materials, Polymer, and a recent issue of 3D Print Industry. Each highlights the team’s focus on the UV-vat polymerization of this liquid resin system. The challenges, he said, are in regulating the viscosity of the reactive resin, and ensuring all materials are soluble and light sensitive. “The approach we have taken is one where we have a mixture of two different things. We have our photoreactive, thermosetting polymer that once cured becomes a soft rubber. To this, we also add a thermoplastic healing agent. We were able to get light to pass through the system, and we achieved that by utilizing polymerization induced phase separation (PIPS). It is a process where the thermoset and thermoplastic materials separate during curing,” he said. “That is key to this whole thing.” PIPS is a single, segmented function where an optically transparent liquid allows light to pass through. By curing the UV resin, the thermoplastic phase separates. Lewis compared that final phase-separated structure to a lava lamp that changes as it is lit or heated. It is similar with the polymers that transform as they are integrated with the 3D-print as each layer is cured. “Earlier work on thermoplastic polymer blends that are able to be processed using conventional techniques like injection molding or extrusion suggested that it was that phase separation that seemed to be driving the self-healing behavior of those systems. That understanding led us down this path of experimentation with this same healing agent and photo reactive polymer system, and then, a little bit of luck,” said Lewis. Ph.D. candidate encourages her class to judge a book by its coverAs a professional paper conservator and color science Ph.D. candidate, Leah Humenuck has studied books from every angle and wavelength. This semester, Humenuck is sharing her love for paper, ink, pigments, and all the material components of a book, in her course, The Secret Lives of Books, a special topics elective offered by the museum studies program in the College of Liberal Arts. She is gaining hands-on experience from the other side of the classroom, working with undergraduate students, sampling an academic career, and adding to her résumé. While the evolution of the book has been a global accomplishment, Humenuck focuses on book development in the Western world and the influence of parchment, which shaped the form, Gutenberg’s game-changing printing press, and the rise of paper. Her class teaches students how to assess a book through its materials and construction. Trends in book development point to available materials and choices often based in practicalities, she said. “There’s more than one way to read a book,” Humenuck said. She alternates her lectures with lab experiences that focus on handling rare books, mixing pigments, learning about book storage, and papermaking. “I think the best way to interact with history is to do the history,” Humenuck added. Christis Shepard, a fourth-year museum studies major from Bayonne, N.J., is enjoying the deep dive into the history of making books. “We’re currently learning about medieval books, the inks medieval scribes and artisans used, and the techniques used in creating parchment,” Shepard said. “It makes me appreciate the ease we have today in making books and that many of these old books managed to survive into the modern day.” Humenuck’s class meets in Wallace Library and frequently visits the Cary Graphic Arts Collection, RIT’s special collection of rare books, and graphic design and printing history. “I wanted to create a class that would intersect with the Cary Collection,” Humenuck said. “I tell my students, ‘While you’re here, use the Cary Collection because it’s phenomenal.’” Humenuck developed the special topics class at the suggestion of Juilee Decker, director of museum studies and co-director of the Cultural Heritage Imaging lab. Decker knew of Humenuck’s interest in an academic career. Liam Myerow A student in the Secret Lives of Books course creates pigments in a medieval method by combining the powdered pigment with a binder in the glass jar. “I enjoy tapping into what students are doing at the graduate level and seeing how they might inform what we’re doing in museum studies,” Decker said. “I thought that Leah’s expertise as a book and paper conservator would provide a materials perspective on a topic that is related to museum studies.” With a focus on libraries, archives, and museums, and a tech-infused approach to liberal arts and sciences, RIT’s museum studies program is one of the few undergraduate degree programs of its kind in the United States, Decker added. Interdisciplinary in nature, the program draws upon expertise from multiple colleges and divisions with a book niche. Steven Galbraith, curator of the Cary Graphic Arts Collection, teaches a course about the history of the book from a curatorial perspective, and faculty at the Image Permanence Institute offer a course about preservation and collections care. “Leah has served as a mentor and an internship supervisor for a number of my students,” Decker said. “I work with her in a research capacity, so I am aware of her excellent scholarship ethics and her keen eye toward mentoring and developing lifelong learning goals for people.” The path to becoming a college instructor is different for every Ph.D. student. The Secret Lives of Books is Humenuck’s first experience writing a syllabus and planning a curriculum for a semester-long class. Decker gave her guidance about classroom parameters and syllabi. She has also sat in on Humenuck’s classes. “It’s common that there’s not a precursor to teaching,” Decker said, reflecting on her doctoral degree at Case Western University. “There isn’t a formal class that says, ‘This is how you become an instructor now that you want to share your knowledge of this topic.’” The opportunity to teach builds upon Humenuck’s experience gained through her many guest lectures and talks, conference presentations, an internship program she created for museum studies, and her semester as a graduate teaching assistant for the Fundamentals of Color Science course. Christie Leone, assistant dean of the RIT Graduate School, said there are a lot of opportunities for graduate students to gain hands-on teaching experience by working as graduate teaching assistants under the supervision of a faculty mentor. Graduate teaching assistants are required to take a training course, GTA Foundations, offered by the Graduate School in collaboration with the Center for Teaching and Learning. The class provides basic background information and introduction to the responsibilities of a graduate teaching assistant at RIT. In addition, some colleges and departments offer their own training specific to their discipline. Humenuck’s class is giving her a multidisciplinary teaching experience. The elective has drawn 17 students from a variety of majors and with different opinions on materials for preserving information. “Being able to answer questions and pull a class together with students having different perspectives is something I really enjoy,” Humenuck said.

Ph.D. candidate encourages her class to judge a book by its coverAs a professional paper conservator and color science Ph.D. candidate, Leah Humenuck has studied books from every angle and wavelength. This semester, Humenuck is sharing her love for paper, ink, pigments, and all the material components of a book, in her course, The Secret Lives of Books, a special topics elective offered by the museum studies program in the College of Liberal Arts. She is gaining hands-on experience from the other side of the classroom, working with undergraduate students, sampling an academic career, and adding to her résumé. While the evolution of the book has been a global accomplishment, Humenuck focuses on book development in the Western world and the influence of parchment, which shaped the form, Gutenberg’s game-changing printing press, and the rise of paper. Her class teaches students how to assess a book through its materials and construction. Trends in book development point to available materials and choices often based in practicalities, she said. “There’s more than one way to read a book,” Humenuck said. She alternates her lectures with lab experiences that focus on handling rare books, mixing pigments, learning about book storage, and papermaking. “I think the best way to interact with history is to do the history,” Humenuck added. Christis Shepard, a fourth-year museum studies major from Bayonne, N.J., is enjoying the deep dive into the history of making books. “We’re currently learning about medieval books, the inks medieval scribes and artisans used, and the techniques used in creating parchment,” Shepard said. “It makes me appreciate the ease we have today in making books and that many of these old books managed to survive into the modern day.” Humenuck’s class meets in Wallace Library and frequently visits the Cary Graphic Arts Collection, RIT’s special collection of rare books, and graphic design and printing history. “I wanted to create a class that would intersect with the Cary Collection,” Humenuck said. “I tell my students, ‘While you’re here, use the Cary Collection because it’s phenomenal.’” Humenuck developed the special topics class at the suggestion of Juilee Decker, director of museum studies and co-director of the Cultural Heritage Imaging lab. Decker knew of Humenuck’s interest in an academic career. Liam Myerow A student in the Secret Lives of Books course creates pigments in a medieval method by combining the powdered pigment with a binder in the glass jar. “I enjoy tapping into what students are doing at the graduate level and seeing how they might inform what we’re doing in museum studies,” Decker said. “I thought that Leah’s expertise as a book and paper conservator would provide a materials perspective on a topic that is related to museum studies.” With a focus on libraries, archives, and museums, and a tech-infused approach to liberal arts and sciences, RIT’s museum studies program is one of the few undergraduate degree programs of its kind in the United States, Decker added. Interdisciplinary in nature, the program draws upon expertise from multiple colleges and divisions with a book niche. Steven Galbraith, curator of the Cary Graphic Arts Collection, teaches a course about the history of the book from a curatorial perspective, and faculty at the Image Permanence Institute offer a course about preservation and collections care. “Leah has served as a mentor and an internship supervisor for a number of my students,” Decker said. “I work with her in a research capacity, so I am aware of her excellent scholarship ethics and her keen eye toward mentoring and developing lifelong learning goals for people.” The path to becoming a college instructor is different for every Ph.D. student. The Secret Lives of Books is Humenuck’s first experience writing a syllabus and planning a curriculum for a semester-long class. Decker gave her guidance about classroom parameters and syllabi. She has also sat in on Humenuck’s classes. “It’s common that there’s not a precursor to teaching,” Decker said, reflecting on her doctoral degree at Case Western University. “There isn’t a formal class that says, ‘This is how you become an instructor now that you want to share your knowledge of this topic.’” The opportunity to teach builds upon Humenuck’s experience gained through her many guest lectures and talks, conference presentations, an internship program she created for museum studies, and her semester as a graduate teaching assistant for the Fundamentals of Color Science course. Christie Leone, assistant dean of the RIT Graduate School, said there are a lot of opportunities for graduate students to gain hands-on teaching experience by working as graduate teaching assistants under the supervision of a faculty mentor. Graduate teaching assistants are required to take a training course, GTA Foundations, offered by the Graduate School in collaboration with the Center for Teaching and Learning. The class provides basic background information and introduction to the responsibilities of a graduate teaching assistant at RIT. In addition, some colleges and departments offer their own training specific to their discipline. Humenuck’s class is giving her a multidisciplinary teaching experience. The elective has drawn 17 students from a variety of majors and with different opinions on materials for preserving information. “Being able to answer questions and pull a class together with students having different perspectives is something I really enjoy,” Humenuck said. Men's tennis drops home match to conference rival UnionROCHESTER, NY - The RIT men's tennis team (3-4, 0-3 Liberty League) fell to Liberty League foe Union College (3-0, 2-0 Liberty League) from the Midtown Athletic Club Sunday afternoon. Union would win two of three doubles points. RIT's Brennan Bull and Jacob Meyerson earned RIT's lone doubles point in a great...

Men's tennis drops home match to conference rival UnionROCHESTER, NY - The RIT men's tennis team (3-4, 0-3 Liberty League) fell to Liberty League foe Union College (3-0, 2-0 Liberty League) from the Midtown Athletic Club Sunday afternoon. Union would win two of three doubles points. RIT's Brennan Bull and Jacob Meyerson earned RIT's lone doubles point in a great... Women's tennis suffers loss to Skidmore in Liberty League openerROCHESTER, NY - The RIT women's tennis team (4-2, 0-1 Liberty League) dropped its Liberty League Conference opener, 9-0 to defending champion Skidmore College (5-0, 4-0 Liberty League) from the Midtown Athletic Club Sunday afternoon. Skidmore would take the first three doubles points. At first doubles, Anne Taylor and Kristen Zablonski put...

Women's tennis suffers loss to Skidmore in Liberty League openerROCHESTER, NY - The RIT women's tennis team (4-2, 0-1 Liberty League) dropped its Liberty League Conference opener, 9-0 to defending champion Skidmore College (5-0, 4-0 Liberty League) from the Midtown Athletic Club Sunday afternoon. Skidmore would take the first three doubles points. At first doubles, Anne Taylor and Kristen Zablonski put...